|

|

|

|

Anyone who wishes to produce On Earth Deceived : Life v. Greed may do so free of charge, no further permission required. Please proceed and enjoy! www.meaningism.org

|

|

|

|

All of the illustrations used in the play On Earth Deceived : Life v. Greed are received with grateful thanks from the esteemed artist of Hyderabad, Sri Narasimha Rao Pinisetty.

This play is based in part on another entitled W O E (West of Eden) written by William T. Durr in 2011, unpublished. Portions of this play are copied or adapted from W O E. Another text, a Muslim Sufi work of the 10th century, entitled "The Letter of the Animals" which was later translated and adapted by Rabbi Anson Laytner and Rabbi Dan Bridge and published in 2005 as a play entitled "The Animals' Lawsuit Against Humanity: A Modern Adaptation of an Ancient Animal Rights Tale" contributed background research to this play. W O E and "The Animals' Lawsuit Against Humanity" examine relationships between nature, humans and God in the context of the Abrahamic faiths from a "western perspective." This play, On Earth Deceived : Life v. Greed, examines those same relationships in the context of meaningism and asks the question : Are humans a force for good? On Earth Deceived : Life v. Greed is written primarily from a South Asian perspective and published on the internet in 2012 at the website : www.meaningism.org.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| On Earth Deceived : Life v. Greed is based on a South Asian system of village justice known as a Panchayat. This system was used throughout South Asia's Hindu regions prior to British rule and is still in use today in some villages to settle disputes — and by the animals of this play — though it has generally fallen into disrepute in modern times. |

|

| A Panchayat consists of five village elders. Each member is known as a Pancha. The head Pancha is the Pramukh who is considered to have the most authority. When hearing disputes, the Panchas meet in a prescribed manner for holding 'court'. The village community assembles and the disputes are heard. |

|

| In this play, a complaint is made against humankind that questions whether they are the force for good that was intended of them in accordance with a mandate long ago given to humanity by Life. |

|

The following Hindi words are used for which translations are provided below :

- Dikhawa — to show off

- Ganga — Ganges river

- Garu — a Telugu word used to accord respect

- Hamarapani — our water

- Hathi — elephant

- Kumari — Miss

- Maharaja — king

- Pallynagargaon — a compound word composed of three common suffixes (pally, nagar, and gaon) used in village names

- Pancha — a village elder who sits on the Panchayat

- Panchayat — a village authority composed of five village elders

- Pramukh — the chief Pancha and village elder

- Peepal — another common name for a Bodhi or Bo tree (Ficus religiosa)

- Sacred grove — a plantation of trees and shrubs associated with a Hindu temple or shrine

- Sri — Mr.

- Srimati — Mrs.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cast (in order of appearance)

|

|

|

[If not portrayed by human actors, some or all of the animals can be represented in various ways, e.g., 1) puppets, 2) papier-mâché masks on poles, or 3) painted on a background screen.] |

|

Main Characters :

|

|

- Gautam (human) — Abha's husband

- Abha (human) — Gautam's wife

- Farmer (human) — male or female

- Narrator (human) — female or male

- Pramukh (elephant), chief village elder — male

- Mongoose, complainant — male

- Pancha Dolphin, village elder — male

- Pancha Parrot, village elder — female

- Pancha Gray Langur (monkey), village elder — male

- Songbird — female

- Monkey — male or female

- Bodhi Tree, testifier — female

- Vulture, testifier — male

- Donkey, testifier — male

- Alabama Sturgeon (fish), testifier — male

- House Dog, testifier — female

- Venkata (human), testifier — male

- Chameleon — female

- Crested Shelduck (duck), testifier — male

- Goat, testifier — male

- Anthony Opasa (human), testifier — male

- Hathi (elephant), testifier — male

- Pancha Cobra, village elder — female

- Crabgrass, testifier — male

- Toad — male

- Periplaneta (cockroach), testifier — female

- Wise Whale — female

- Crew Member — male or female

|

|

Animals who shout out brief comments from the village assembly :

|

|

- Tortoise

- Street Dog

- Deer

- Pig

- Rabbit

- Elephant

- Fish

- Monkey

- Peacock

- Squirrel

- Eagle

- Sheep

- Tiger

- Chicken

- Wolf

|

|

|

|

|

On Earth Deceived : Life v. Greed

Prolegomenon

Here's a tale told just for you.

It's ages old, about — guess who?

It twists and turns, bores like a screw.

Why should this story interest you?

Some won't hear but those who do,

may find what's thought belies what's true!

Can the meaning of life you have faithfully sought

from knowledge evolved, from debates hard fought,

let arrogance defeat grace, leaving what sacros brought

disavowed by your actions and thus all for naught?

For the anvil of damnation, whereupon greed is wrought,

sears goodness and belies truths taught to souls who've been bought!

|

[The prolegomenon is recited before the curtain rises. An actor can point at the audience as he says "just for you", point to himself as he says "guess who" and motion his hands in a circle as he says "bores like a screw" or use other kinds of motions and expressions to demonstrate the verse. Or, one actor can speak very expressively while another actor acts out the motions.]

|

|

|

[As the lights dim and before the curtain rises, some animal sounds of the jungle are heard along with part of an ongoing conversation in the background.]

|

|

|

"My point is that humans spell their goodness with one o and all along the way reap more than they sow. They act as though they own everything, they don't under . . . "

|

|

|

Act I

Another Day

Scene 1

On the Beat

|

|

|

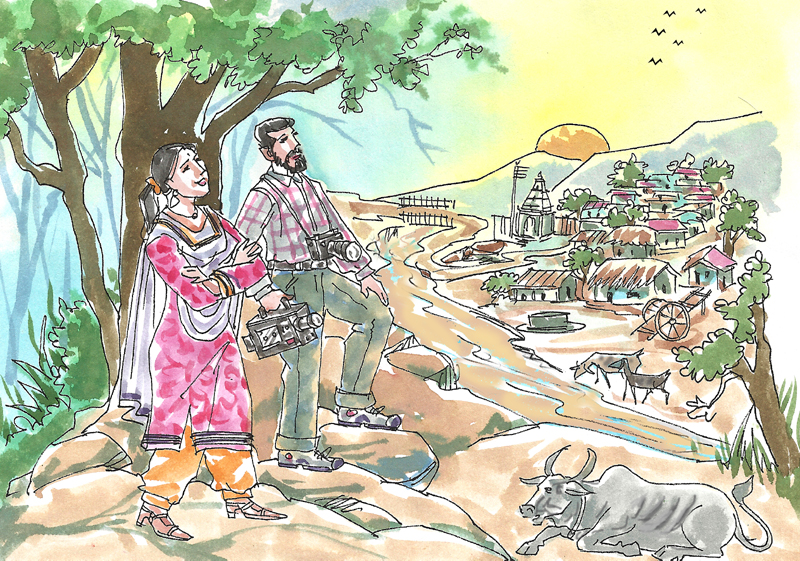

[A young couple are having breakfast on a Sunday morning. The wife, whose name is Abha, is a reporter for a popular TV station, and her husband, Gautam, is keen to go with her on her assignment. He is a software engineer and green activist. They are sitting at a table eating. He is reading the news on his computer laptop and she is glancing at the newspaper. He looks over to her.] |

|

|

|

| Gautam. | | What a brilliant Sunday morning, a fine day in the making. |

|

| Abha. | | Yes, lovely, isn't it. |

|

| Gautam. | | You were saying last night that today you'll be interviewing some farmers

about climate change and their crops. That village, isn't it the one with a temple inside a jungle — an old sacred grove about a couple of hours from here? |

|

| Abha. | | Yes, that's right. Do you want to come along? Today I can show you how I do my

work. That would be great! |

|

| Gautam. | | Right, but, well, I thought I might walk around in the jungle a bit and see what

animals are there. Is that okay? When do we leave? |

|

| Abha. | | Oh really, Gautam, you're all worried about wild animals when the people who

feed us are barely able to find hope for a brighter future? Some of them are even

committing suicide you know. |

|

| Gautam. | | That's not fair, Abha. It seems to me there's a bigger problem going on. Everything is suffering. |

|

| Abha. | | [says indignantly] Right, the animals too. |

|

| Gautam. | | Right. The damage we've caused to the environment is a crime itself. What

might Mother Nature do with a pest that's out of control like us? Huh? Might we be lucky enough to get a fair trial? |

|

| Abha. | | Well, I'm no pest . . . . Okay, fine, so go talk to the animals about it. I'm talking to people. I don't get paid for holding a microphone to the lips of an elephant! I mean . . . . okay, let's not argue, sorry. I know, it's your . . . . [picks up a box]

Happy birthday Gautam! Let's go out to dinner when we get back. |

|

| Gautam. | | Should I open it now? |

|

| Abha. | | Let's do that tonight. We've got to get going. The crew will be here any minute, so

hurry up. |

|

| [curtain] |

|

Scene 2

What's Going On?

|

|

|

[They arrive to the village and Gautam walks off following the temple trail into the jungle. Abha proceeds to interview the villagers. She is standing with a group of farmers, their faces full of desperation, holding the microphone and explaining why she is there.] |

|

|

|

| Abha. | |

Hi, I'm the regional reporter for FYI News who called you about doing an

interview on the affects of changing weather on your crops.

|

|

| Farmer. | | Yes, good that you've come, there is so much to tell. |

|

| Abha. | | What have been the consequences of climate change for you? |

|

| [All the farmers begin to speak at once, Abha puts the microphone to one of them.] |

|

| Farmer. | | It used to be that only once in many years would we get either a drought or a

flood. During a good monsoon we could make a good living and set

aside some money for the bad years. But now it seems that there is a disaster

every other year and last year we even had a drought followed by a flood — both in

the same year! The money lenders are getting ruthless and really we are feeling

hopeless. |

|

| Abha. | | Then what do you think is the solution for a better future? |

|

| Farmer. | | The government has to make good on their commitments. [The other farmers

standing in the group voice their agreement.] Years ago, we were all supposed to benefit from a massive irrigation project. No more does the Hamarapani river flow to the sea but neither does it flow to us. Others are getting the benefit but not us. You see those hills over there, they're in the way. [The farmer points to some low, rolling hillocks.] They've had problems blowing them up. That is our main problem. They say just wait another year but already many years have come and gone. I don't think the other farmers over there want to share the water. |

|

| Abha. | | Have you given up depending on the monsoon? |

|

| Farmer. | | We'd like to. With irrigation we can expand our farms by clearing those useless scrub jungles, and the animals in there keep eating our crops. |

|

|

[Suddenly, in the background, a couple of women start screaming uncontrollably. Everyone runs over to find a middle aged farmer writhing on the ground suffering the effects of poison he had just consumed. A bottle lies next to his right hand. The lights begin to fade with a final glance at Gautam who is under a tree in the process of slumping over from his meditation posture — falling asleep.]

|

|

|

|

| [curtain] |

|

|

[Before Act II begins, a narrator comes down the aisle and addresses the audience.]

|

|

|

Narrator. | | Thank you for coming to see On Earth Deceived : Life v. Greed. What you

just saw, all five minutes of it, was like a normal play. That is the last you'll see that's like a normal play. What every play asks a person to do is to "suspend your disbelief". You are asked to voluntarily enter into the world of the play and what a fantastic world it can be! This world is one in which plants and animals talk to one another and to us. That's all from me for now. So, as they say, on with the show! [The narrator motions toward the stage and runs back up the aisle.]

|

|

|

|

|

Act II

The Assembly

Scene 1

The Complaint |

|

|

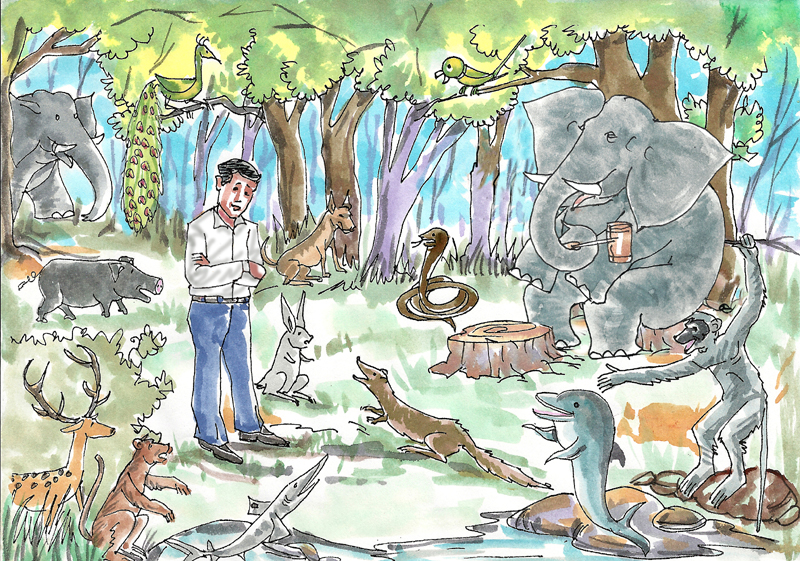

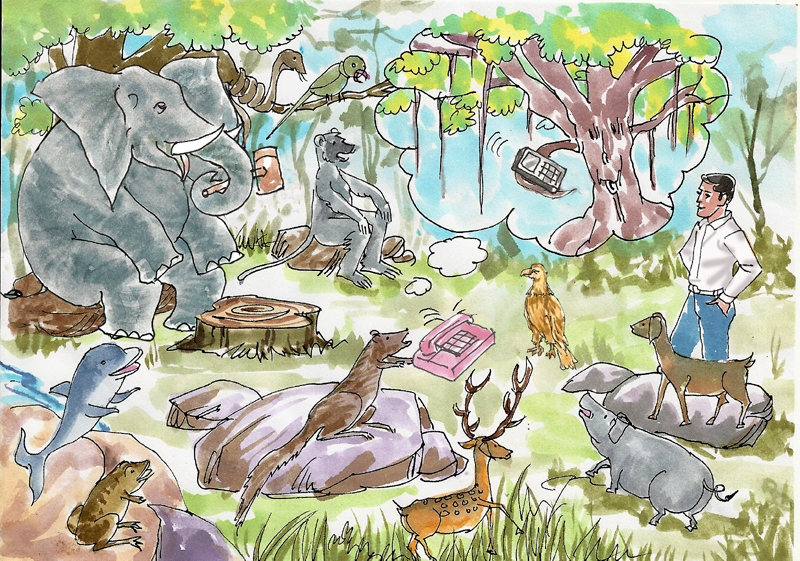

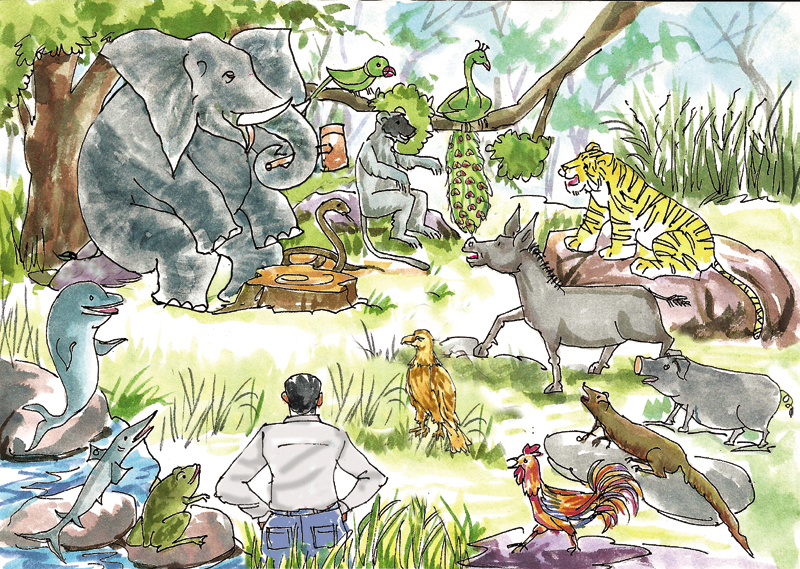

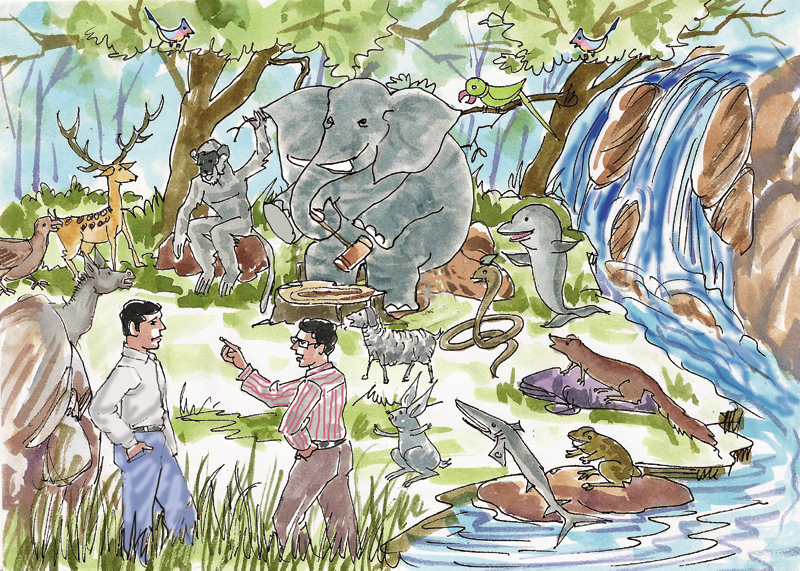

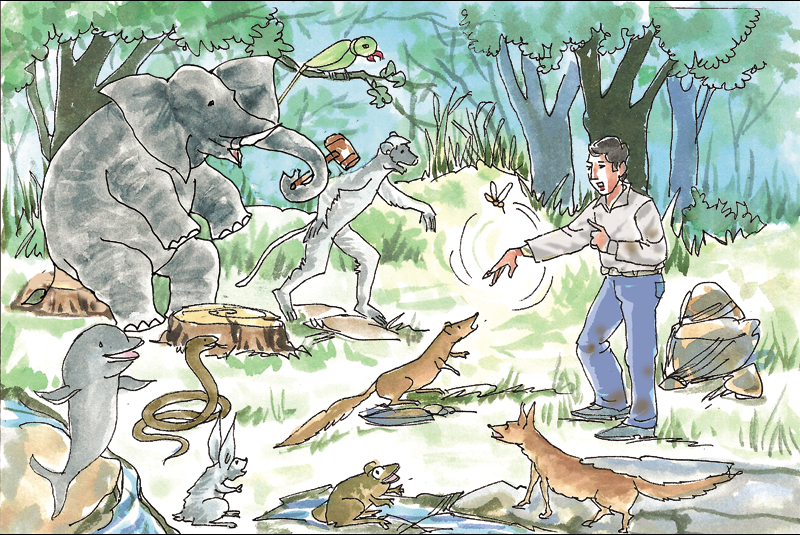

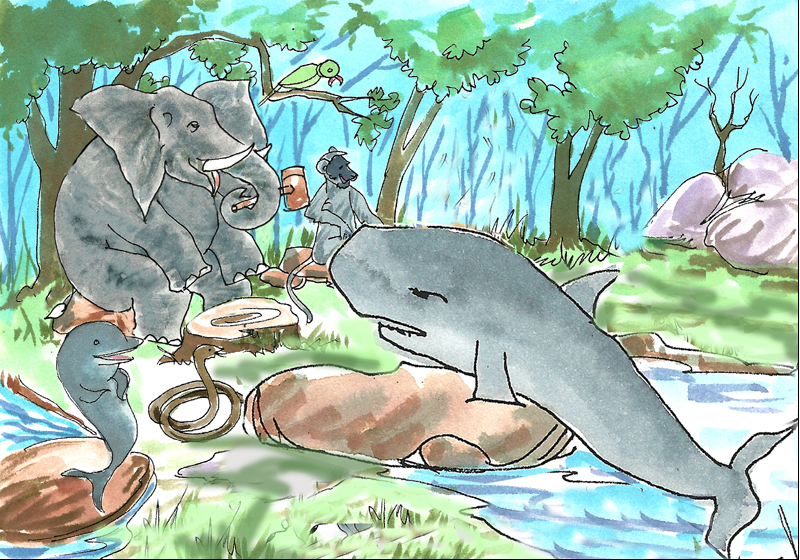

[A village panchayat has assembled with five Panchas. The Pramukh is an Elephant and the other four Panchas are a Cobra, Parrot, Dolphin, and Gray Langur. The dispute is between a Mongoose, the complainant, who is representing non-human life, and Gautam, dazed and bewildered, who has been drafted to represent humankind.]

|

|

| Pramukh. | |

Sri Mongoose, before you proceed with the complaint against humans, I'd like to introduce the other four distinguished Panchas of the panchayat. [pause] Members of the village assembly, along with myself, the elders who shall sit in judgment today are Pancha Cobra, who joins us from the forest floor; Pancha Parrot, from high above in the sky; Pancha Dolphin, who is resting right here on a stump upstream from the river Ganga, and Pancha Gray Langur of the nearby hillslopes. Together, we have observed humans from many perspectives, [The Panchas nod their heads.] over many years, and they are of all kinds. We must base our decision today on whether or not there are enough of the right kind to carry out the responsibility intended of them. [pause] Sri Mongoose, are you ready to proceed with your complaint against humans? |

|

| Mongoose. | |

I am, sir. For the record, I wish to state that this complaint is made on behalf of Life from her home of nature on earth. |

|

|

Pramukh. | |

Very well. [motions to proceed] |

|

| Mongoose. | |

Animals, trees and creatures of the village : While we don't know exactly when humans first appeared on the face of the earth, we do know that until a few thousand years ago they lived responsibly like the rest of us. They were born, they raised families, they died, and like us they returned to the soil. To live, they hunted like we do. They ate plants like we do. They ate other animals like some of us like to do. |

|

| [The Pancha Cobra sitting in the Pramukhment becomes mildly agitated — she hisses. The Mongoose clears his throat. The Pramukh calls for order.] |

|

| Mongoose. | |

As I was saying, the humans, like many of us [he looks pointedly at a chicken in the front row of the assembly and she flutters her wings], they ate other animals and lived in caves for shelter. As some of us do, they made nests, which now they call houses, and so forth. Until recent times, their total population stayed around ten million and, all things being equal, humans, along with all other animals, creatures, and plants lived in the lap of nature. But then, about 10,000 years ago, they began on their present course. It led them to create the disaster that is causing so much damage to all our homes today. Humans tell us that it is good for the earth that they are here, that they alone are endowed with the right to manage the world. It's their privilege and responsibility they say. |

|

| [A tortoise shouts out.] | |

As if we're lucky and should be grateful to them! They alone are responsible for the mess we're in. Look at me, do I need a house? Why they're all inside out and backwards if you ask me. The crap comes out their mouths. |

|

| Pramukh. | |

Quiet! Members of the village assembly, please do not interrupt Sri Mongoose. There will be time enough for you to speak during these next couple of days. Sri Mongoose, continue. |

|

| Mongoose. | |

But it seems to us that over the last few thousand years, and particularly the previous thousand years, that many of their ugliest tendencies have become worse. They've not improved. The biggest problem came when they started to put a value on everything, including us. Never mind the size of the value, it's just that they are compelled to put one. Otherwise, they can't make sense of anything. That means those of us who get labeled as worthless end up getting our habitats destroyed. I don't know what's worse because if they declare you as valuable then you get consumed. It's either hell or processing. Their next problem is that they have to understand everything and when they don't understand very well, but they think they do, we suffer terribly. After everything has gone wrong, they call their misunderstandings "mistakes." We call them disasters. But it gets even worse! What they agree they don't understand they make up stories about. Some of these stories become their beliefs and that's when it can get really weird. They call it sacrifice. We get dressed up and treated very nicely and then unspeakable things happen to us. Now, we, the rest of life, are left doubting our own futures. So, this is our question : Are humans a force for good in the world? |

|

| Pramukh. | |

That doesn't sound like a complaint. |

|

| Mongoose. | |

Well, humans were supposed to be a force for good! Now, we have to decide if they really are, or, if they aren't, then we must ask if they could ever be? |

|

| Pramukh. | |

Sri Mongoose, yes, you are right, they were supposed to be a force for good. Members of the assembly, before proceeding further, I'd like to put this discussion in historical context. [pause] Long ago, following the last major extinction . . . |

|

| [Gasps, whimpers and yelps are heard from the village assembly.] |

|

| Pramukh. | |

Oh, sorry for using that word, I'll be more careful. To continue, long ago there

was a meeting of the Great Council of Life. They met to decide which form of life

should be made responsible for helping the rest of us survive the next major

catastrophe. Massive loss of life, of an uncontrollable and arbitrary kind, has happened too many times in our history and too often destroyed the painstaking progress of evolution or set it backwards in as much the same way as an earthquake can reverse the flow of a river. The Great Council of Life decided that one of life's forms should be promoted above all others as a consequence of being blessed with the privilege of responsibility. After evaluating several drafts of humans, the present form was proposed and brought forth as our caretaker. But, as a matter of truth, responsibility came with a choice, the choice of acting irresponsibly. What we see today is that humans may not have matured enough as a species to handle this choice. They should have learned how to make wise choices by now. We have to decide if they can learn at all. If not, we may be on the verge of an unnatural, human induced mass extinction. |

|

| [Once again there are gasps and whimpers from the village assembly.] |

|

| Pramukh. | |

Sorry! sorry . . . . We can't wait another millennium until their understanding of goodness and responsibility catches up with their power to dominate. We have to decide now whether a correction to their attitude, their greedy ways, needs to be recommended to the Great Council of Life. This is the dilemma before us. Let us proceed. Do we have a human that can represent them? |

|

| Mongoose. | |

Yes sir, we do, we found one this morning under a tree. His name is Gautam. |

|

|

|

| Pramukh. | |

Gautam! That Gautam . . . . [The Pramukh says with a big smile on his face.] |

|

| Mongoose. | |

Oh, no Pramukh Garu, not that one, same name but a different man, as different as these times. |

|

| Pramukh. | |

[talking to the assembly] The last time we discussed this was indeed a different time. It was an age when we all felt comfortable with humans living alongside us. But we also got our first clues, or you could say our first fears, that what they really had in mind was to subdue, conquer and exploit us well beyond their needs. A holy man among them named Gautam could sense our concern, and he came to discuss our distress. A fine example of a human, among the best, and he said he would work with his kind and teach them to live within their needs and some of them did. But not all of them, and most of them don't now. So, we shall see what this Gautam has to say. Sri Mongoose, what more have you to say? |

|

| Mongoose. | |

Just a few more words, Pramukh Garu. Over the last few thousand years, many humans lost goodness, they lost their way, all this started when they began acting like they owned the earth and us too! They even made claims on each other. Never do they have enough. |

|

| [A street dog shouts out.] | |

But we have our territories too. I fight for mine and piss to make a point. |

|

| [There is a ruckus, the Pramukh bangs his gavel.] |

|

| Mongoose. | |

They aren't satisfied with just a territory. The problem is that they're able to live anywhere and everywhere — from the coldest tundra to the warmest jungle. And, it's everything they're after. I'm talking about damming up rivers and wiping out habitats to the extent that many fish, beasts and butterflies have no place to go and so they die off; its about spilling tons of oil along coastlines and fouling our dwelling places with their garbage and sewage. It's about making so much noise that birds can't hear their songs. It's about putting so much pollution into our air that our whole world is warming up and changing faster than we can evolve! Do you get it? |

|

| Street Dog. | |

Yes, I get it. [He shakes his head back and forth.] |

|

| Mongoose. | |

So, until recent times these gross things didn't happen. |

|

| Pancha Dolphin. | |

Then how did it get started? |

|

| Mongoose. | |

About 10,000 years ago humans started to build fences. They decided to keep us animals off what they called their land. |

|

| [A deer shouts out.] | |

I could hop over the fence. |

|

| [A pig shouts out.] | |

I couldn't. |

|

| [A rabbit shouts out.] | |

I could crawl under it. |

|

| [An elephant shouts out.] | |

I couldn't. |

|

| [A fish shouts out.] | |

A fence? Is that like a net? |

|

|

|

| Pramukh. | |

Order, order! [pause] You may proceed, Sri Mongoose. |

|

| Mongoose. | |

My point is they began to believe they owned the earth — all of it! [All the animals in the village assembly nod their heads and make their respective sounds, excitedly.] |

|

| Pramukh. | |

[bangs gavel] Order! Order! [looks over at the Mongoose] Sri Mongoose? |

|

| Mongoose. | |

I'm nearly through, sir. Once they got in charge, all the other creatures and animals and plants became objects of their desires! Humans began to build cities. They built big fences around their cities and called them walls. |

|

| [A monkey shouts out.] | |

And then they made zoos with cages for us! |

|

| Mongoose. | |

They created armies that fought huge battles and destroyed grazing grounds. They made animals into slaves and called it "animal husbandry." |

|

| [A peacock shouts out.] | |

Well, there isn't any human I would want as a husband! |

|

| Pramukh. | |

Yes, indeed, they used to force us to fight in their wars, wicked and bloody battles that made absolutely no sense and the losers would be made into slaves — they even made slaves of their own kind. |

|

| Mongoose. | |

But then as bad as that was, it got awful! Three hundred years ago they started what they called their Industrial Revolution. They invented the steam engine. To make the heat for steam they needed coal. They mined coal from hills. They lost thousands of their own lives as they did this but never mind that, they called it the 'pride of progress' or 'price of progress' or something like that. Next, they invented the stream engine to generate electricity from flowing water. That changed our streams and rivers into huge stagnant pools which drowned all that had been living on the land, and their dams blocked our passageways. Many times they even forced their own people to move out of the way. |

|

| Pramukh. | |

Sri Mongoose, may I remind you that this is not a history lesson. This is not an anthropology class. This is about whether humans are, at their very nature, good. Come to the point!

|

|

| Mongoose. | |

May I just come to what I was leading up to sir, and then I'll address that question? |

|

| Pramukh. | |

[exasperated] Please. |

|

| Mongoose. | |

Thank you, sir. After humans had their industrial revolution, they invented ways to expand it and take more than even a pig could imagine! [All the animals in the village assembly look at the pig who buries his head in his hoof.] For instance, in a place called Bihar, to get coal, humans took huge machines and dug up and threw away whole mountainsides and mountaintops. Gone are the trees. [The birds get agitated.] Gone are the deer trails. [The deer get excited.] Gone are the lakes. [The fish flap their fins.] Gone is everything! [The whole village assembly erupts. The Pramukh bangs his gavel.] So, Pramukh Garu, these are the reasons I doubt human claims to goodness. Animals, trees, and creatures of the assembly, as much as this is about what humankind has done, it is more about what is behind their nature. Humans are living beyond the laws and limits of nature herself. Humans cause the needless and merciless deaths of billions of earth's plants, animals and creatures. They waste earth's resources; they destroy our habitats; they pollute our skies; they foul our water. |

|

| [Pancha Parrot shouts out.] | |

And they're very noisy! |

|

| Mongoose. | |

Humans are far from a source of goodness, they've become a pest that wages specicide on planet earth! [The villagers are buzzing among one another.] |

|

| Pramukh. | |

Specicide? What is specicide? |

|

| Mongoose. | |

Specicide is the careless disregard or purposeful abuse of one of our kind leading to the elimination of an entire species. Yes, it can happen naturally, but lately most of what's gone missing is because some of us have misplaced our fate in our faith in humanity. Each year there are more and more humans and less and less of us! |

|

| Pramukh. | |

Thank you, Sri Mongoose. [The Pramukh looks pointedly at Gautam.] Sri

Gautam, it appears that the complaint against humans is that they have badly neglected, if not altogether abused, their responsibility to other life, not to mention the earth itself, so much so that it is difficult to see how they could be the force for good that was intended of them. Your job is to convince us otherwise and restore our faith in the leadership of humans.

|

|

|

|

| Gautam. | |

Pramukh Garu, distinguished members of the Panchayat and village assembly, I had no idea I'd be here today! These are all very serious charges that you are very right to raise, and it's a debate I agree I must be a part of. It's challenging to be a human. Oh that I were a seal in the sea or a bird in a tree, or even a bee! |

|

| Pancha Parrot. | |

You say debate? Debate! This isn't some academic deeebaate. This is it. We're fed up! This is very real to us. We live with the consequences every day. Right now! You, your kind, stand accused here, and we're looking for answers, apologies, changes — a new beginning — right actions. You've got a lot of explaining to do if we're not to ask Life herself to bring disease and pestilence upon humans. By your very own definition, you should consider yourselves as a plague upon our mother earth! |

|

| Gautam. | |

Yes, there are some laws of nature that we have violated, [Members of the village assembly nod their heads and chatter.] some species we have eaten to extinction or thoughtlessly destroyed. |

|

| Pancha Gray Langur. | |

Thoughtlessly? You're supposed to be the best thinking, the most thoughtful of all animals! |

|

[Some members of the village assembly jump up and wave signs, the Pramukh bangs his gavel and calls for order. The villagers persist and grow louder. The signs read :

-

Humanity = Insanity

-

Peepal, YES

People, NO

-

Homo sapiens or Homo stupidians?

-

Stop Humankind Now

-

Government by the animals for the people!

-

God — if you like them — take them!

] |

|

|

| Pramukh. | |

Quiet! Order, order! Sit down. |

|

| Gautam. | |

Pramukh Garu, members of the village assembly, I find it difficult to speak today. I'm not ready to represent humans let alone defend them. Many of the things you say are true. But please, you see, I was sitting under a Bodhi tree next to a temple when suddenly some monkeys brought me here. I need some time to prepare, collect my thoughts, and examine the facts. I had no idea the animals of the world were this upset. Can I have time to prepare? |

|

| Pramukh. | |

Very well, we will adjourn for two days. Sri Gautam, prepare as best you can to represent humankind and explain in their view, or by the view of any other life form, how humans are a force for good in the world or at least possess the potential to be so. |

|

| [curtain] |

|

|

|

|

|

Scene 2

A Tip

|

|

|

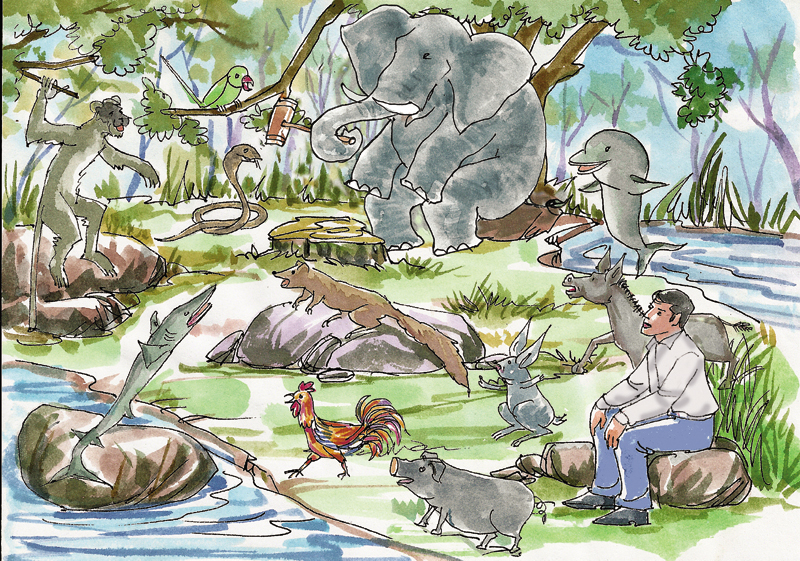

[During these two days, Gautam spends much of his time preparing under a tree while listening to music through earphones. Just above him a songbird alights on a branch.] |

|

|

|

| Songbird. | | Hi there! [Gautam looks around.] Here, look up here. You're Gautam, that's your name. Right? |

|

| Gautam. | | Yes. [Gautam says as he removes his earphones.] |

|

| Songbird. | | So you've got a tough job ahead of you! |

|

| Gautam. | | I guess word has gotten around. You tell me, what possible defense can I make without getting egg on my face? |

|

| [The songbird looks insulted.] |

|

| Gautam. | | Oh, gee, sorry about that! |

|

| Songbird. | | Never mind, I'm not here for polite talk. I have a couple of points for you. Gautam, have you ever heard the 'song of life'? |

|

| Gautam. | | Huh? [pause] I've heard beautiful songs from birds like you. Is that one of yours? |

|

| Songbird. | | And we've heard the songs of humans, from their temples to their parties. Some sounds more pleasing than others. But, most of your throbbing sounds spoil the inner ear, so much so that humans struggle to hear what's important. |

|

| Gautam. | | The inner ear? Where's that? You mean something I should be hearing from within. |

|

| Songbird. | | No, not exactly, but wearing those boomphones aren't going to be of any help. [pause] Listen, the song of life is an enthralling song entirely composed of sounds without frequencies that you can't hear without tuning the inner ear. |

|

| Gautam. | | How is that done, and why should I want to hear this kind of song? |

|

| Songbird. | | Walk alone in the forest or sit by the sea and when your mind tells you that a sound is there though it's one you can't hear, listen, meditate transparently, be fully receptive until you discover sounds that together add up to what, in your terms, would be described as the most fantastic symphony imaginable. |

|

| Gautam. | | Uh, but in order to hear a sound, first there must be a frequency. Right? There's no other way. |

|

| Songbird. | | Hum, okay, let's try this. When you speak silently to yourself or think in a quiet moment, do you hear your thoughts, or is it only your words? Right, there are no frequencies, unless . . . . unless you believe in thought frequencies. There lies the door to your inner ear. Now, take the next step Gautam. Can you hear thoughts without speaking to yourself, [pause] can you hear without words, [pause] can you hear without yourself? Who then is hearing? Where [pause] is what you are listening to? Alas, you've found the place of Life's transference. Listen there for Life's messages. The forest and the sea are abuzz with them, they come by way of music, in the midst of this music. |

|

| Gautam. | | Music? Music I can't hear? |

|

| Songbird. | | Right, not the physical kind of music used for dancing, not the thoughtful music used during contemplation, not the soothing music for relaxation, not the spiritual music used during worship but music nonetheless though it is unlike any of these. |

|

| Gautam. | | Does this music have words? |

|

| Songbird. | | No, it's pure music, the first music. This music is the language of emotion, of Life itself for which we can only struggle to find words. It is of the thought that was before there were words that is much deeper, much richer than thinking merely in sequences of actions. Let this music guide your actions. Translate these messages into words so that your kind may be able to understand. |

|

| Gautam. | | Understand what Srimati Songbird? [The songbird flaps her wings once.] No, please don't fly off, tell me . . . . understand what? |

|

| Songbird. | | [said as the songbird is getting ready to fly off] The truths, empathy first among them — they will educate your conscience and help you understand your place among us. Matters of relationship, respect, union, caring, well being . . . . All of life is a testament to interdependency and must not be held hostage to your worship of capitalism that is greed by a few nor your faith in democracy that is greed by the many. Together these practices have left no room for us. Do you love Life or just yourselves? |

|

| [Just as the songbird flies off, a monkey arrives with a message from the Pramukh.] |

|

| Monkey. | | Sri Gautam, I have a message, the Pramukh requires your attendance at the assembly tomorrow morning at 8:00 am. |

|

| Gautam. | | I'll be there, ready or not, I'll be there. |

|

| [curtain] |

|

|

|

|

|

Scene 3

The Dispute

|

|

|

[Two "days" have passed and the village assembly reconvenes. The Pramukh addresses the assembly.]

|

|

| Pramukh. | | We are assembled here today to ascertain whether or not humans are a force for good. Sri Gautam is speaking on their behalf. [pause] Sri Gautam, are you ready to proceed? |

|

| Gautam. | | Yes, Pramukh Garu. [pause] What I heard two days ago helped me understand that the biggest grudge you have against humans . . . |

|

| Pancha Parrot. | | Grudge? Grudge! We don't have some sort of gruuuudge! You stand accused of gross selfishness and massive arrogance! Just how will you answer to that? |

|

| Gautam. | | I agree that humans take more than they deserve with little regard for the impact that has on you. That, in fact, we often act in total disregard of you. That makes us irresponsible. [pause] Humans are complicated. Our sense of responsibility causes us to plan for the future and so, like some other animals, we store up the resources we depend on so we can be sure they are there when we need them. |

|

| [A squirrel shouts out.] | | Fine, I do that too, but when I no longer need something or misplace it, a tree grows instead. When you guys don't use what you've set aside, it turns into even more pollution than you caused to produce it. You are careless and wasteful. |

|

| Gautam. | | Sometimes we are, but in spite of all our misdeeds, I ask you to imagine a world without humans. |

|

| [A monkey shouts out.] | | I can! |

|

| [A pig shouts out.] | | No competition, imagine that! |

|

| [The Pramukh bangs his gavel.] |

|

| Pramukh. | | Stop interrupting Sri Gautam and let him make his points. |

|

| Gautam. | | It would be a world without the Taj Mahal or the Great Pyramids. It would be a world without jets, [An eagle flutters her wings but says nothing.] a world without trips to the moon. |

|

| [A sheep shouts out.] | | Go there! Just go! |

|

| [A monkey shouts out.] | | They've done that. |

|

| [A sheep shouts out.] | | Oh. [slight pause] Then stay there! |

|

| [Again the Pramukh calls for order, banging his gavel.] |

|

| Gautam. | | No museums, no universities, no hospitals. |

|

| [A monkey shouts out.] | | And no zoos! |

|

| [The whole village assembly cheers. The Pramukh bangs his gavel twice.] |

|

|

|

| Pramukh. | | Animals of the village assembly, I am well aware that not one phrase uttered by Sri Gautam explains what good humans are to anybody other than themselves, but it will take time to explore this issue. Sri Gautam, you may proceed and stay on point please. |

|

| Gautam. | | I admit that humans take more than they give. We take more than we leave. We think mostly on our terms and not on animals' or nature's terms. So, admitting that, as we proceed, I ask the members of the village assembly to try to imagine with me a new world : It would be a world where the will of some of our best people becomes the way of us all. A meaningful world where nature is truly revered and animals not only have respect but also have rights — rights that are just as important as human rights. A world where Life itself is worshiped as a fount of ever evolving forms, fueled by the elements, and cherished by all. |

|

| [The village assembly is stunned and silent.] |

|

| Pramukh. | | Thank you, Sri Gautam, we hope that is possible someday, but we must base our assessment on today. The testimony we receive over the next day will help us draw our conclusions. Please understand, humans have spoken so eloquently before. [pause] Sri Mongoose, please call your first testifier. |

|

| Mongoose. | |

My first testifier is the oldest and largest of the testifiers, a Bodhi tree. It is impossible to bring her here, and so we must have a long distance conference call. |

|

| [sounds of dialing on a speakerphone] |

|

|

|

| Bodhi tree. | | Hello |

|

| Mongoose. | | Hello, is this Srimati Bodhi tree? |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | Yes, indeed. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Greetings Srimati Bodhi tree, I had contacted you a few days ago about . . . |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | Yes, that's right, I stand ready to testify. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Thank you for participating today, may we have your full name and address? |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | I am a Bodhi Tree from Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka originally from Bodh Gaya, India. |

|

| Mongoose. | | [looks puzzled] Right. How old are you? |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | I am about 2,700 years old from seed, a bit less from a twig. |

|

| Mongoose. | | How old, madam? We just need one answer please. |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | 2,700 years old — give or take a few hundred years — it all depends on who you want to count and which you means me. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Well then, just exactly where are you from? |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | I have roots in several places. |

|

| Mongoose. | | What, you exist in different places at the same time? |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | Is that so difficult to believe, or is it that you have to pin me down? |

|

| Mongoose. | | May I ask, Srimati Bodhi Tree, just how do you get around? |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | It's a long story, we don't ordinarily travel, but I've been well cared for ever since the Buddha sat under me for several weeks in search of truth and achieved enlightenment. I'm in a few more places now and planted back in Bodh Gaya where I had perished. Fortunately, a monk had helped me put down roots in Sri Lanka before that happened. I may well be the original clone, certainly the oldest. Thanks to humans, I and my kin have been treated nicely due to our good fortune to have been in contact with this one most honourable man. You could say he was one in several hundred million. Lucky for us! |

|

| Mongoose. | | Have most other kinds of trees been as fortunate as you? |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | No, I am sorry to say, not at all, most have not been able to stay their ground. I have a few old colleagues here and there around the world, some much older, but I've heard through the grapevine of terrible atrocities committed against trees. You should talk to one of my good friends in California who is a 3,800 year old Redwood. A giant among us with many stories to tell. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Can you tell us one of them? |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | Yes, gladly. Four hundred years ago the Redwoods occupied about two million acres and provided a place to live for the Spotted Owl, Brown Pelican, Bald Eagle, Black-tailed deer and forty other mammals not to mention many, many other creatures. But sadly, during the last two hundred years, 96% of the Redwoods have been cut down. Terrible for them and those who loved them. |

|

| Mongoose. | | How so? |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | Over many centuries a balance had been worked out between the flora and fauna. The native humans who lived there also had become a part of that balance. |

|

| Mongoose. | | So why did things change? |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | New people came who had a different attitude. |

|

| Mongoose. | | How different? |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | As different as night is from day. For them, Redwoods were not trees, they were so many feet of lumber. For them, animals were not lives, they were things in the way. Attitude is a big thing. These new people had what we call the G.O.D disorder. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Please explain. |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | G.O.D is short for Greed Overpowering Dharma which is to say me before the consequences, "it's my God given right." In fact, they're so proud of this disorder that many of them worship it in a faith called capitalism. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Where did this G.O.D attitude come from in your view? |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | That's a good question. As we understand it, a long time ago those humans who lived on the northern and eastern shores of the Mediterranean Sea decided that they would conquer all they could. They would take charge of fields and forests; they would mine the soil; they would capture creatures of the sea. They decided that everything was theirs. |

|

| Mongoose. | | So, what did they do to trees? |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | We were among the earliest victims. For instance, the tall, beautiful, millennia-old Cedars of Lebanon were cut for temples, palaces, and mansions. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Anywhere else? |

|

| Bodhi tree. | |

Yes, the Romans deforested North Africa for the same reasons. The Maharajas and British did the same in India. Then, what little was left, their Green Revolution finished off. The agriculturalists try to convince you that they save trees by making farms more productive but all they really end up growing is more people who then cut us up for more fuel to make more bricks for their houses and to cook their meals. Even more land is cleared for crops or to build houses for more and more people which also requires more lumber. Another word for humans should be 'more'. There should be a tax on agriculture to pay for growing more trees if you ask me. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Has no one tried to stop them? |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | When I was a youngster and just 688 years old, that would be 2,012 years ago, I heard a story that was making the rounds. |

|

| Mongoose. | | What was it? |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | The story was that a Jewish Rabbi named Jesus might stop the cutting. It seems that he had spent some time alone with trees and shrubs in the wilderness and he often went to gardens to pray. They said that he understood Life like the Buddha before him. He felt very conscience about it all and took upon himself a great burden on behalf of the whole of humanity. He had reached the zenith of empathy and responsibility and was the greatest example of the nexus between the two. |

|

| Mongoose. | | That sounds hopeful. What happened? |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | He was going to try to bring change for trees and the whole of nature by changing the way people think, but his enemies, some selfish humans, got a hold of him and killed him and then hung him on a wooden cross. It was horrible. Then they wrote that he wanted it that way. Imagine that! The problem is that he didn't write down what he wanted. That would have been the greatest use of paper ever! |

|

| Mongoose. | | So, the G.O.D attitude goes way back? |

|

| Bodhi tree. | | Yes, when humans became human they proclaimed that God gave them dominion over the earth and still they keep asking for more in the name of God — they have a profound disorder. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Thank you Srimati Bodhi Tree. Pramukh Garu, I have no more questions. I just want to point out that much of this discussion will be, as Srimati Bodhi Tree just said, about attitude. Much of what is deemed either possible or impossible is really about attitude as the members of the village assembly will see. |

|

| Pramukh. | | Sri Gautam, please call your first testifier. |

|

| Gautam. | | I call on the Indian Vulture. [The vulture alights at the front of the assembly.] Please tell us your place of residence, Sri Vulture. |

|

| Vulture. | | I live at the Vulture Conservation and Breeding Centre in Pinjore, Haryana. |

|

| Gautam. | | Why do you live there? |

|

| Vulture. | | It's a nice gated community, good food, safe sex, and we feel respected there. |

|

| Gautam. | | Have humans been good for you? |

|

| Vulture. | | Some are good to us, such as those that take care of us, but their jobs exist only because most humans don't care about us. Humans never used to be an issue but over the last few decades we've barely been able to survive around them. When we go out to do our job we get poisoned. |

|

| Gautam. | | On purpose? |

|

| Vulture. | | No, by accident. I think there's no intent just disregard and carelessness. |

|

| Gautam. | | What is your job? |

|

| Vulture. | | We eat leftovers. |

|

| [A peacock shouts out.] | | You mean disgusting, rotting flesh! No wonder you're so ugly. Fresh meat does wonders for me as you can see. |

|

| Vulture. | | Madam, we'll eat dead peacocks too or would you rather lay around stinking up the place? |

|

| [Peacock shouts out.] | | Ha! [said in an indignant huff] |

|

| [A tiger shouts out.] | | Yes, I remember them too, they used to be such a bother as I was finishing a meal. |

|

|

|

| [The Pramukh bangs his gavel once.] Order! |

|

| Pramukh. | | [says coyly] Many of us know of your affiliation with death but exactly how is it that there are so few of you now? |

|

| Vulture. | | We are around 98% fewer now, almost gone altogether. |

|

| Gautam. | | Why? |

|

| Vulture. | | It took some figuring out by a team of human scientists dedicated to our welfare. You see, the farmers had been drugging their livestock with a drug called diclofenac which reduces joint pain in order to keep the animals working longer. After they were worked to death, we would fly in and do our job but it turns out that this drug would cause our kidneys to fail. Humans finally admitted they made a mistake and after a couple of years they banned the drug in law. |

|

| Gautam. | | Good that! |

|

| Vulture. | | Well, they banned it in law, that's on paper, but many of them are still using it today. Most humans don't care about us, not in the least, and the few who do are feeding the few of us that are left. Imagine that! We used to be masters of the end game. We vultures numbered in the millions across several species inhabiting South Asia. Still, they haven't stopped the manufacture of the drug, just the use. |

|

| Gautam. | | [sounding frustrated with the outcome of his examination] I am finished with my questions, Pramukh Garu. |

|

| Pramukh. | | Sri Mongoose, do you have any questions for Sri Vulture? |

|

| Mongoose. | | Yes I do, sir. |

|

| Pramukh. | | Please proceed. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Did humans kill vultures in any other ways? |

|

| Vulture. | | In the good old days, whenever we were busy eating road kills, we'd sometimes get run over. Both my aunt and uncle were killed by one of their murder-cycles that run along their paths that they cover over with concrete and asphalt. They race along them at speeds up to 120 kilometres per hour. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Would you please tell the village assembly what is a murder-cycle? |

|

| Vulture. | | Of course. A murder-cycle is something with two or four — the big ones have eighteen — wheels that travels at enormous speeds. We vultures have tried to out-fly them but we always lose. Sometimes the murder-cycles hit animals, even men or women, and they keep right on going, as though nothing happened. |

|

| [An eagle shouts out.] | | I fly over them. |

|

| [A fish shouts out.] | | I swim by them. |

|

| [A chicken shouts out.] | | I can't. |

|

| Pramukh. | | Members of the village assembly, you must refrain yourselves. |

|

| [A pig shouts out.] | | But they don't! |

|

| [Pramukh bangs his gavel twice.] |

|

| Vulture. | | You can't tell which murder-cycle will hit you from one that will not. So we call all of them murder-cycles. The murder-cycles travel on paths that go to where humans have made their nests of walls. Wall nests are all over the place. |

|

| Mongoose. | | What are wall nests like? |

|

| Vulture. | | A wall nest is thousands of blocks by hundreds of feet in every direction. As ugly as a nightmare, with a paved path to where they park their murder-cycles. There, the owners mate and have offspring for which they build schools and recreation parks and shopping centers that use up more and more of our shopping area. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Sri Vulture, what is the purpose of your life? |

|

| Vulture. | | To make good on death, I suppose. |

|

| Pramukh. | | Thank you, Sri Vulture, for telling us your views on humans. [pause] Sri Gautam, please call the next testifier. |

|

| Gautam. | | Yes, sir. Next, I call Sri Donkey to testify on behalf of the working animals. [pause] Sri Donkey, may I have your name? |

|

|

|

| Donkey. | | I'm called "stubborn" most of the time, sometimes I'm called "Jack." |

|

| Gautam. | | Tell us, what do you think of humans? |

|

| Donkey. | | I don't think much of them at all. They try to push me around every now and then. They think their burdens are my burdens. |

|

| Gautam. | | And what do you do about that? |

|

| Donkey. | | I just stand there. |

|

| Gautam. | | And? |

|

| Donkey. | | And what? I just stand there. They think I'm stupid. Do I look like some sort of stupid ass to you? I don't really have anything more to say. [He walks away.] |

|

| Mongoose. | | Don't you ever feel exploited as a beast of burden? |

|

| [The donkey looks back as he talks.] |

|

| Donkey. | | Just who are you calling a beast! I think you must mean mules. Mules are exploited, if you ask me, they are one mixed up kind of dumb ass, go talk to them. |

|

| Gautam. | | Hey, Sri Donkey, you aren't asked to carry all of our burdens, not the burdens of responsibility! |

|

| Donkey. | | Right, not my job, I only carry the burdens you people take seriously. That is whatever you can sell regardless of the happiness you can't buy! |

|

| [The donkey leaves.] |

|

| Pramukh. | | Gentlemen, I hope our next testifier has a few more points to make! |

|

| Mongoose. | | Yes, indeed, Pramukh Garu, he is the Alabama Sturgeon. [pause] Sir, may I proceed with the questioning? |

|

| [The sturgeon has a noticeable black 'box' on its left fin.] |

|

| Pramukh. | | Yes, proceed. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Sri Alabama Sturgeon, please state your name and address. |

|

| Alabama Sturgeon. | | My name is Alabama Sturgeon and my address is the Alabama and Cahaba Rivers. I am an American. |

|

| Mongoose. | | I understand that in June 2009, a court declared 326 miles of the Alabama River and the Cahaba River as a critical habitat. Is that correct? |

|

| Alabama Sturgeon. | | Yes. Actually it is 245 miles of the Alabama River and 45 miles of the Cahaba River. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Well, that doesn't add up does it? Was there any objection to this ruling? |

|

| Alabama Sturgeon. | | Yes, there was. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Please describe it. |

|

| Alabama Sturgeon. | | The first thing that happened is that industry declared this place as critical to them and declared that we do not exist. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Did you take offense to that? How did it make you feel? |

|

| Alabama Sturgeon. | | We were all insulted! Perhaps they declared we do not exist because over the last ten years 80% of our population has been caught from over fishing. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Is that the official reason for why it was claimed that you do not exist? |

|

| Alabama Sturgeon. | |

No. What they claim is that we are the same as the Mississippi Shovelnose Sturgeon. Imagine that! How would you like to be called a shovelnose? |

|

| Mongoose. | | Pramukh Garu, on behalf of the Shovelnose Sturgeon, I ask the assembly to ignore that last comment. |

|

| Pramukh. | | Yes indeed. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Sri Alabama Sturgeon, have you ever been personally injured or offended by a human? |

|

| Alabama Sturgeon. | | Yes I have. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Please describe what happened. |

|

| Alabama Sturgeon. | | In 2007, I was caught and examined extensively. Then a scientist extracted millions of sperm from me. Then he placed this [here the sturgeon holds up his left fin] tracking device on my fin. |

|

|

|

| Mongoose. | | Did you give consent for either procedure? |

|

| Alabama Sturgeon. | | No sir. |

|

| Mongoose. | | What happened? |

|

| Alabama Sturgeon. | | Well, they kept track of me for a year — most of 2008. But during that year I was having an affair. Imagine being tracked while you're, you know, surfing the waters so to speak. So, somehow I managed to disable the battery. Then I heard about this assembly and asked if I could come and testify. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Since you are out of the water, how are you breathing? Don't you require water? |

|

| Alabama Sturgeon. | | [says with a big grin] Yesterday, I took a very deep breath. |

|

| Mongoose. | | So, your existence has been denied; your sperm has been taken; then you were involuntarily attached to this tracking device and your privacy was violated. |

|

| Alabama Sturgeon. | | That's about it. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Sri Alabama Sturgeon, what is the purpose of your life? |

|

| Alabama Sturgeon. | | I love the water — especially if it is clean and clear. I love the tadpoles in the spring. I love the sun warming the water in April. I love the autumn leaves that float until they get soaked and then sink to the bottom and make river mud. |

|

| Mongoose. | | I asked you what is the purpose of your life? |

|

| Alabama Sturgeon. | | Well, I just live. I never thought about that. |

|

| Mongoose. | | [turns toward Gautam] Your turn. |

|

| Gautam. | | Sri Alabama Sturgeon, would you describe yourself as a litigious fish? |

|

| Alabama Sturgeon. | | I don't understand. |

|

| Gautam. | | My research shows that you've been in court over fifteen times. Is that correct? |

|

| Alabama Sturgeon. | | I have been in court many times but not because I violated laws. It was because of what, in all due respect, your people have done to us. |

|

| Gautam. | | Well, in the year 2000, the American Secretary of the Interior took the Fish and Wildlife Service to court claiming that it had violated the Endangered Species Act. And on May 24, 2002, in the Northern District Court of the U.S. Federal Court in Birmingham, with an amicus curiae filed by the Pacific Legal Foundation, you were in court again. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Pramukh Garu, the number of times that either the testifier or his species has been in court is irrelevant. Please cease this line of questioning. |

|

| Pramukh. | | [looking at Gautam] What do you say? |

|

| Gautam. | | Pramukh Garu, what I am pointing to is this : There are also humans who have the Alabama Sturgeon's best interests at heart. |

|

| Mongoose. | | As in all grilled up for their bellies! |

|

| [Gautam stares at the Mongoose.] |

|

| Gautam. | | Sri Sturgeon, have you ever heard of Ray Vaughn? |

|

| Alabama Sturgeon. | | Yes, he's the talk of the Alabama River fish. |

|

| Gautam. | | And what do you know about him? |

|

| Alabama Sturgeon. | | That he is our friend. |

|

| Gautam. | | That is correct. [pause] Pramukh Garu, I would like to point out that Ray Vaughn, an environmental lawyer in Montgomery in the year 2000, sued the Fish and Wildlife Service and began the actions on behalf of the Alabama Sturgeon who we are discussing. Animals do have some very good friends. They are special people among the human race. Today, the river is a better habitat for the fish because of people like Ray Vaughn. |

|

| Pramukh. | | That was fascinating testimony. I hope we can find more testifiers with stories like those of Sri Alabama Sturgeon. Thank you Sri Alabama Sturgeon. |

|

| Gautam. | | Pramukh Garu, man's best animal friend would like to speak next. |

|

| Pramukh. | | What animal is that? |

|

| [A house dog steps forward.] |

|

| [A wolf shouts out.] | | Oh, of course, a dog, you dogs are everywhere they are. You're just like them! Practically inseparable. |

|

| [A street dog shouts out.] | | No, not all of us are like that! I'm a dog of the street, the Alpha on Centre & Main to be exact, and that's no dog standing there, that bitch is a P.E.T., a Pathetic Egocentric Traitor. Sure she is going to tell you how much she loves humans, all pets do. |

|

|

|

| House dog. | | You shush, you jealous mutt. I am a proper house dog and proud of it. |

|

| Pramukh. | | [bangs gavel] Order. Order! |

|

| [The wolf shouts out.] | | Right, a pet, a P.E.T.! |

|

| Pramukh. | | Silence! Gautam, continue. |

|

| Gautam. | | Srimati Dog, what do you think of humans? |

|

| House dog. | | Humans treat us with so much affection, surely they must be a force for good. Many of us, the better and best looking of us, just couldn't imagine life without them. Otherwise, we would be as beat up and as bad looking as Tarzan there. |

|

| [The street dog shouts out.] | | That's Alpha! |

|

| Gautam. | | What is the purpose of your life, Srimati Dog? |

|

| House dog. | | It is to be loved and provide comfort. Pramukh Garu, I think humans are just great. We are cared for very well. No complaints. |

|

| [Suddenly, a man, looking as though in the throws of death (with a stare of resolute desperation), walks near the front of the village assembly, oblivious to all that is going on.] |

|

| Mongoose. | | [speaking with some urgency] Excuse me, please, Pramukh Garu, I may have a surprise testifier and with all due respect to Sri Gautam, I'd like to ask this person who is just passing by to comment on the human condition. |

|

| Pramukh. | | Yes, that's important to understand about humans. |

|

| Mongoose. | | The villagers tell me he is a farmer named Venkata . . . . Sir. Sir! [The Mongoose shouts in the direction of the farmer.] |

|

| Pramukh. | | [signaling to the farmer] Sir, would you be willing to testify before this assembly? |

|

| Venkata. | | About what? |

|

| Pramukh. | | Your life. |

|

| Venkata. | | Okay, though there is not much to say, and I'm busy on my way. |

|

| Mongoose. | | I'll keep it brief. I call farmer Venkata to testify. [pause] Sri Venkata, may we know your village? |

|

| Venkata. | | I came from Pallynagargaon. |

|

| Mongoose. | | What kind of village is that? |

|

| Venkata. | | Just a place among places, nothing more. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Sri Venkata, do you do good for people and for nature? |

|

| Venkata. | | I most certainly did. I grew the food they ate, and I irrigated lots of wasteland to make it productive. I have fed lots of people and their livestock over many years. |

|

| Mongoose. | | What crops do you grow? |

|

| Venkata. | | Rice and pulses. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Do you find it rewarding? |

|

| Venkata. | | I kept busy, but no, not for the money. I cultivated many acres of land at a loss for so many years that all I ever owned was debt. It never paid the bills, nobody would ever pay me enough. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Then why do you keep at it? |

|

| Venkata. | | It's what I knew how to do, and so I worked hard at it. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Then is it fulfilling? |

|

| Venkata. | | [agitated] What's your point? It's what I decided to do for a living and that's why I did it! |

|

| Mongoose. | | So you are a farmer and farming is you. |

|

| Venkata. | | That's right, along with my family, and of course, my pride. |

|

| Mongoose. | | It's your purpose. |

|

| Venkata. | | I did it on purpose, yes. |

|

| Mongoose. | | What are happy times for you? |

|

| Venkata. | | Childhood, harvests, festivals, marriage, childbirth — these were happy times for me amounting to a few precious weeks out of the year. |

|

| Mongoose. | | [asks frustratedly] Why do you always respond in the past tense? |

|

| Venkata. | | You have not asked me about crop failures, unhappiness, about desperation, misery, worries, insecurities, threats and fears, stress and poor health. These have always overwhelmed those few benefits. In the end, I just lived, existed, like my livestock. Hopeful but finally hopeless, yesterday I tried to end my life. I drank a bottle of poison. My family took me to hospital where I lay dying. If you are asking me if humans are good then all I can say is that most of them are about as good for each other as pests are for crops. Excuse me, but I must get on with my death now. Do you know if I have any say in what I can be in my next life, I'd like to try something else! |

|

| [Everybody looks around puzzled at each other.] |

|

| Pramukh. | | [whispers to the other Panchas] Sadly, he forgot to make farming his purpose. |

|

| Mongoose. | | [asks hesitatingly] Sri Venkata, just one last question please. For what purpose did you live? |

|

| Venkata. | | I already told you. I was a farmer. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Right, you did. Okay, let me ask it this way: Why did you come from Life? |

|

| Venkata. | |

Huh? Why ask me? I was taught that God had that answer. He knows my purpose and reason for being. You must submit to God. Right? [pause] But, sometimes I tried to find the answer. That was mostly during the happy times, the good times, when enough was going right that I started to think about what was behind it and how to keep it going. |

|

| Mongoose. | | And then what happened? |

|

| Venkata. | | Stuff went wrong again, and so I'd go out for a drink with my buddies to figure it out. |

|

| Mongoose. | | What happened then? |

|

| Venkata. | | Not much. You know, life's not fair. That's what we decided, and it's in God's hands anyway. |

|

| Pramukh. | | Excuse me gentlemen. Sri Venkata, it's how you decide to live life that can be unfair to yourself and to others. Life itself is fair but how it is lived shows how well you have understood its purpose. That's where fairness is determined. That's where problems can become un-problems. There you can find the cradle of love and goodness. Cultivate these for their steadfastness in times of need. Ask yourself this : Do you live life to live off of it or as a part of it in support of it? Embrace, worship and immerse yourself in Life. This is your greatest birthright. |

|

| Venkata. | | Even if that were true, it's too late for me! It seems that I only lived to be used and finally abused. I really must move on now, I'm through, wasted, just finished, it's useless to continue. You see, all I really had left was faith in me and now I'm done. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Didn't you do pujas and pray to God? |

|

| Venkata. | | [says as he is walking off] Yes, regularly. Got your answer, mongoose? |

|

| Mongoose. | | Yes, got it, neither you nor your God was of much help to your self. |

|

| Pramukh. | | Gautam, have you any . . . ? |

|

| Gautam. | | No, sir, but where's the sympathy? This man is practically dead! |

|

| Pramukh. | | It is indeed saddening, Sri Gautam. Disappointing, in fact. Sri Venkata committed murder. Must Life be so disguised by the mask of you upon it that you live in ignorance of its essence your whole life long? |

|

| [As Venkata leaves, a chameleon comes front and centre.] |

|

|

|

| Chameleon. | | Pramukh Garu, excuse me please. I have a point to share here, sir. I just have to say . . . |

|

| Pramukh. | | [The Pramukh interrupts and asks in an annoyed tone.] Yes, Srimati Chameleon, what is it? |

|

| Chameleon. | | Sir, I have patiently observed humans, and I know for a fact that they cannot live without hope. If they become hopeless they will die of ill-health or even kill themselves out of despair. Hope is their personal caretaker. For me, it's rather simple, if I feel out of place I just change my colour. For them, it's more complicated, hope is the bedrock of the human condition. Since it has exclusively to do with their future, they constantly dwell on how to assert it and in the process screw up their futures and ours too I might add. We simply dwell in our dwellings. |

|

| Pramukh. | | According to Sri Venkata, most humans seem to care for little, let alone show much empathy, even for their own kind. Are humans any good for themselves? I'd say what good is hope then? They need to care today. |

|

| Chameleon. | | Sir, as for their hope, it needs a solid basis in faith. A faith in truths founded upon beliefs born of meaning like our faith in meaningism. Those raised from infancy through childhood who have not benefited from the nurturing of nature, from active engagement with 'the wild,' [She uses her hands to signal quotes.] have nearly disengaged as adults from their place in the ecology of Life and its teachings. Yes, they have lost faith. Actually, they may never have found it. Many of them suffer from a syndrome known as CLUTTER which is the Careless Love of Useless Things, Thoughts, Emotions and Rhetoric. Yet others succumb to a disgusting social disease known as POOP — People Obsessing Over People — they are all the time bothered over the affairs of one another forever scheming even at the expense of their brothers never mind much to do about anything other. As a wise songbird once said, if they can understand the meaning of their purpose and make it their own they will care for themselves today and find fulfillment in their future. Until they realise this, hope or worry is all that keeps most of them going. |

|

| Pramukh. | | Thank you, Srimati Chameleon, for your comment. I note your point about the difference between human nature and mother nature. Let's keep this pretence of theirs in mind. [pause, looks to the Mongoose] Sri Mongoose, please call the next testifier. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Will the Crested Shelduck please come forward? [pause] May I have your name and address? |

|

|

|

| Crested Shelduck. | |

Some call me the Korean Mandarin Duck, but I prefer the name Crested Shelduck — it's less ethnic. My range is eastern Russia, northern China, North and South Korea and northern Japan — but I haven't been seen in any of these places since 1964. |

|

| Mongoose. | | They tell me that once you ranged widely. |

|

| Crested Shelduck. | | Yes, my ancestors did. They lived around much of the Pacific Rim. I still have lots of surviving cousins : The Paradise Shelduck, the Australian Shelduck, the South African Shelduck, the Ruddy Shelduck, the Rajah Shelduck . . . |

|

| Mongoose. | | How many of your kind still exist? |

|

| Crested Shelduck. | | Many think we're extinct. I [He pats his chest.] may be the last living Crested Shelduck! |

|

| Mongoose. | | Since you have so many cousins, who are not on the endangered species list, then why are the Crested Shelducks almost extinct? |

|

| Crested Shelduck. | | We were collectable. They killed us, they gutted us, stuffed us, and mounted us in order to show us off. [pause] The fewer we became, the more they loved us! |

|

| Mongoose. | | Why did the collectors go after Crested Shelducks? |

|

| Crested Shelduck. | | We are adorable, simply the best. |

|

| Mongoose. | | The best? How? |

|

| Crested Shelduck. | | Good looking! [He says slowly and loudly looking pointedly at the Mongoose, frustrated that he doesn't seem to get it.] Our colors are white and gray and black and brown. We males have an iridescent green patch on our speculum and, along with the ladies, green tufts protrude from our heads. [He nods his head.] Just look at this handsome orange beak. We've been portrayed in Chinese tapestries and one of us, of course, a stuffed male, made it all the way to the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen. |

|

| Mongoose. | | So, you may be the last living specimen of the best looking duck in the world. |

|

| Crested Shelduck. | | Yes, best looking, and I deserve the best museum they have to offer. |

|

| Mongoose. | | I beg your pardon. [pause] Sri

Crested Shelduck, what is the purpose of your life? |

|

| Crested Shelduck. | | [in a cocky manner] Sri Mongoose, what is the purpose of your life? |

|

| Mongoose. | | I live for one moment at a time and right now I live to ask you what is the purpose of your life. Please answer my question. |

|

| Gautam. | | Pramukh Garu, why does this question have to be asked? |

|

| Mongoose. | | I ask this because humans do not ask it! It never occurs to them. They don't even ask it of themselves. |

|

| Crested Shelduck. | | In answering the question about my purpose, it wouldn't do any good to say that I live for the sake of my kind. We're gone . . . . if I live to be 100 years old, there's no one left to mate with, to lay eggs, to have young. It's done! We're done! |

|

| Mongoose. | | So what keeps you going? |

|

| Crested Shelduck. | | I live for the game! I live for the sport! That's all that's left! |

|

| Gautam. | | Pramukh Garu, may I? |

|

| Pramukh. | | Yes, proceed Sri Gautam. |

|

| Gautam. | | I have two questions. First, is it possible that you simply do not reproduce like other ducks do? That your decline is because you do not reproduce much? |

|

| Crested Shelduck. | | Our last appearance was in 1964 on an island south of Vladivostak, Russia. Someone saw a male and two females. |

|

| Gautam. | | Were they there to mate? |

|

| Crested Shelduck. | | Pramukh Garu, do I have to answer that? What about our privacy? |

|

| Pramukh. | | It's not about your privacy — it's about your species. Yes, you must answer. |

|

| Crested Shelduck. | |

Some 'experts' think that we prefer to mate near mountain lakes where we like to go in the warm season. Others think we mate near the sea. What happens is that the female duck prefers to incubate her eggs in the coastal areas. It doesn't take her long to produce the eggs after — do you understand? |

|

| Pramukh. | | Yes, we all understand. |

|

| Gautam. | | I understand that in China, Korea, and Russia in the 1980s that people distributed three million leaflets on your behalf, seeking to protect you. Is that correct? |

|

| Crested Shelduck. | | That happened because in 1982 a Chinese forester ate two of us and didn't discover he had eaten Crested Shelducks until he got back to what they call civilization. The poor man, this was China, 1982, he almost lost his life for that! Of course, it was too late to do any good for ducks. The government only got 81 responses to the 3 million leaflets — but, still, no verified sightings of us since 1964, unless you count the 1991 postage stamp in Mongolia! |

|

| Gautam. | | I have no further questions. |

|

| Pramukh. | | Thank you, Sri Crested Shelduck, you may go. [pause] I have a special request of the village assembly, would someone please testify on behalf of the farm animals? |

|

| [A goat steps forward.] |

|

| Goat. | | I would be pleased to. |

|

| Pramukh. | | Sri Mongoose, would you please take the testimony of Sri Goat? |

|

| Mongoose. | | Yes sir. Sri Goat, why do you live, and please explain why you are always found around humans? |

|

| Goat. | | We live to eat anything and everything we can. Humans are good to us and always show us where to find more food. They care for us day after day. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Is that so? Have you ever wondered why you never see any old goats? Don't goats ever grow old and die? |

|

| Goat. | | No, we don't grow old and die, we just don't. The shepherds have told us this and made it clear we have nothing to fear. Death is of no consequence. |

|

| Mongoose. | | Is that so? Shepherds, what are they? |

|

| Goat. | | They are a kind of human who loves us just the way we are. They're not so complex like other types of humans. They even give our milk to their children. |

|

| Mongoose. | | But if you never die then doesn't it get crowded at times? |

|

| Goat. | | Yes, at times, but every once in a while a big group of us is sent to where the grass grows greener on the other side of some distant hill. You wouldn't believe how happy the humans get about that and they don't even eat grass! We do miss our buddies for a while but there's more for us to eat in the meantime, and we know they're happier where they've gone. I'd say we share our lives intimately with humans and they curry favour with us in return. |

|

|

|

| [A villager shouts out.] | | You mean curry flavour! [Roars of laughter come from the assembly.] |

|

| Goat. | | What's that, what did he say? |

|

| Pramukh. | | Never mind that. Thank you Sri Goat, you may return to your flock. |

|

| Gautam. | | Pramukh Garu, I asked a friend of mine to come and help explain how some humans make their best efforts to do good. I have such a gentleman here with us today. May I ask him to testify? |

|

| Pramukh. | | Please do. |

|

| Gautam. | | Good afternoon. May we have your name and address? |

|

| Anthony Opasa. | | My name is Anthony Opasa. My address is Cebu Island, part of The Philippines. |

|

| Gautam. | | Sri Opasa, what is your occupation? |

|

| Anthony Opasa. | | Currently I am a community organiser. |

|

| Gautam. | | Sri Opasa, please tell us how you came to be a community organiser. |

|

| Anthony Opasa. | | Well, 20 years ago, on a trip to Norway, I discovered that the Norwegians thought of their county not just as their own but also as a land that belonged to their children and even to their unborn children. In other words, Norway was for their descendants as well as themselves. |

|

| Pancha Gray Langur. | | What am I hearing? Is he telling us that even unborn humans have rights that we don't have in the first place! |

|

| [All of the village assembly buzz in agreement.] |

|

| Gautam. | | May I continue, Pramukh Garu? |

|

| [The Pramukh signals to proceed.] |

|

| Gautam. | | [looks at Anthony Opasa] You were saying that the land belonged to the children and unborn children. To descendants! |

|

| Anthony Opasa. | | Yes, and I realised that this should be true in the Philippines too. We were taking the future away from our descendents! So I organised the Philippine Ecological Network. We decided we had to save what was left of our forests. |

|

| Gautam. | | How did you go about it? |

|

| Anthony Opasa. | | First, we tried suing the logging companies for breaking environmental laws. |

|

| Gautam. | | And? |

|

| Anthony Opasa. | | It didn't work. Big shots would make a few phone calls and our suits would be delayed; then they'd get lost in the bureaucracy. Or worse, we would get charged with harassment. We knew what was going on but what could we do? Then we went to court with "Minors Opasa", a legal suit against the government for allowing grown-ups to sell virgin forests to logging companies. |

|